Outside the hustle and bustle of Brazil’s tourist hotspot, Rio de Janeiro, over 130 000 people call the sprawling Maré favela of Rio home. Favelas are considered to be the slums or low-income informal areas of Brazil. They have been historically neglected by the government, leaving people struggling to access their basic human rights to water, sanitation and representation.

While the favela communities may be ignored by the government, a local organisation, Data Labe, is using the power of data journalism and narrative storytelling to re-write these, often forgotten, histories of the favelas, and the people who call them home. Through this, Data Labe is working to empower and uplift these communities, fighting for a new legacy of social agency and political representation.

Data Labe is one of the members of the Internews Health Journalism Network (HJN) and is a featured presenter at the April HJN Flashtalk on Citizen-Led Digital Health Innovations for their new initiative called CocoZap, which uses Whatsapp to collect citizen-generated data on sanitation in Maré.

Becoming characters of their own history

“When we started to access this space, we started to rethink the city, rethink our bodies because we started to talk [for] ourselves about our lives, about our rights. When we started to think about Data Labe as a laboratory that works with journalism and data, it’s about how we can dispute our own history through the narratives, the stories and through the data. How can we humanise the data, how can we get some face, some colour, gender, sexuality to data, to numbers,” says Gilberto Vieira, one of the organisation’s founders.

Data Labe started in 2015 with just five people focussed on data journalism. In 2016, they hosted a data journalism training course for 15 young people from the favela communities, which led them in search of more funding to continue this type of training. Over the years, Data Labe’s trainees have gone on to work in large newsrooms all over Brazil.

Data Labe’s work dives into four key issues: gender and sexuality, race, territory (favelas vs urban areas) and the environment. Vieira explains that these topics are connected, for example if you’re a black womxn in Brazil that lives in a favela, you won’t have the same access to sanitation compared to other people of different races and genders.

CocoZap

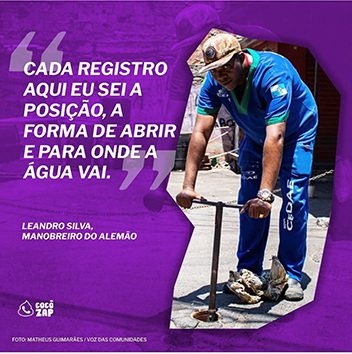

“We started to think, how can we produce data with the help of the population. We saw with this opportunity that we could talk about the importance of data [and] about ourselves. If we have data about ourselves we can fight for rights. If you see [an] open sewer, or mountain of garbage, you can send it to me [who has been part of this community] and I will post it on the database and we can fight for this problem,” says Vieira.

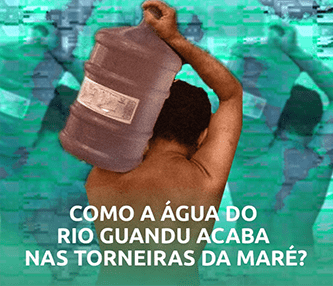

The lack of data about favela communities is a huge problem, and Data Labe is working to understand and fill this information gap. Vieira says that a lot of the poorer parts of Brazil are counted for the national census by helicopter because of fear and hesitancy to go into these areas to adequately collect data.

Vinícius Lopes joined Data Labe at the beginning of the year to assist Vieira with CocoZap. “Our data is very crucial at this time to try and get some data and to find out how people are dealing with a lack of sanitation, [and] a lack of environmental rights. The COVID-19 pandemic sets us in a place that we have to focus on these issues because these issues are often neglected because the government doesn’t have much interest,” he says.

Lopes lives in Conjunto Esperança, one of the smaller favelas in Maré. “We don’t experience many problems with water availability or basic sanitation needs like in other places in Maré, but still we know that our sanitation and pipes system barely endure our needs – it’s been made almost 40 years ago and the inhabitants that have been mostly responsible for the maintenance. We also face some problems with electricity – in strong rains or storms, we’ll probably run out of power for a couple of hours,” says Lopes.

“We are living here. We exist. It’s very important to do this job and to try and collect this data from the population that lives here because we try to mingle with them and get them to help us,” he describes.

Response from favela communities

It’s hard to measure the impact of Data Labe’s work, says Vieira, but there are a lot of positive responses and engagement from readers on social media, especially from young people- the organisation’s target audience.

“It’s good that we try to write articles, last year there was an article talking about the history of sanitation in Maré and my grandma and my mother felt seen. They felt that their history was not forgotten and that there is someone paying attention to them, their history and their needs. I think that when we are talking about favelas, it’s often a place that is forgotten, [so] it’s good to have initiatives like this. We are often forgotten so when there are people trying to get rights to these people and do democracy work, or even educational work, it’s good,” adds Lopes.

By Kathryn Cleary