Last week, about two weeks before the February 24th scheduled parliamentary elections in Moldova, Facebook removed 168 Facebook accounts, 28 Facebook pages and eight Instagram accounts active in the country, for engaging in “coordinated inauthentic behavior,” spreading fake and manipulative information. According to Facebook’s statement, some of the inauthentic activity could be traced to real Moldovan government employees.

Facebook’s action, a result of their internal investigation, happened after Moldova’s trolless.com platform, developed with the support of Internews’ MEDIA-M project, reported close to 700 suspected fake accounts and pages to Facebook.

Trolless – from hackathon to reality

In 2016, before Moldova’s last presidential election, a team of young enthusiastic people came to a media hackathon organized by Moldova’s Independent Journalism Center (IJC), an Internews partner, and Deutsche Welle Akademie, with a big idea – to create an application to let ordinary users identify trolls and fake accounts online. Moldova’s information space was drowning in misinformation at the time, and trolling was increasingly threatening real discourse.

“We believed strongly that an app was not enough. We developed a demo version of the web platform trolless.com – which helps identify and isolate sources whose goal is to manipulate and misinform on a mass scale via the news media. Two years later, in 2018, we launched the platform, with a grant offered by IJC, within the MEDIA-M project,” says Trolless co-director Victor Spinu.

The trolless.com platform helps users report and find specific information about profiles identified as trolling or fake accounts. Information, such as from whom the fake account stole an identity, what kind of information they are sharing, and what they are commenting on is available through Trolless.

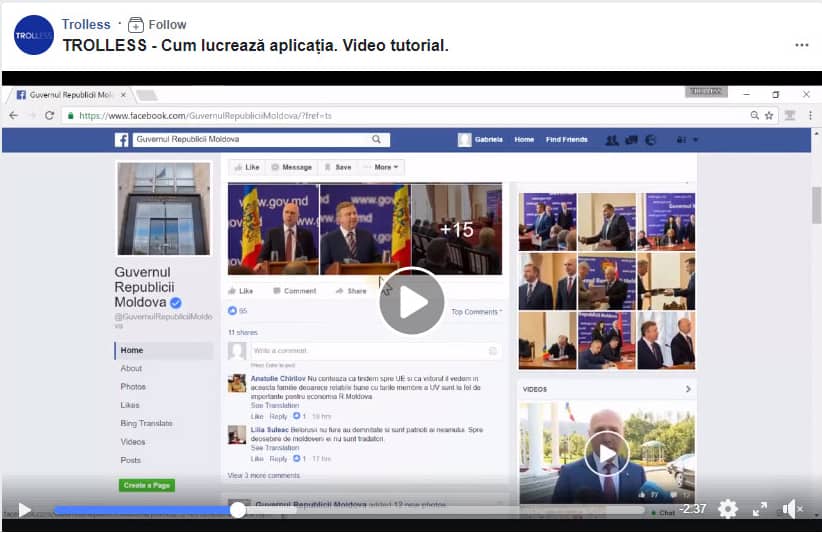

To promote the use of this platform, the Trolless team created a video tutorial and a Facebook page for interacting with users.

Watch the video tutorial:

After users download and install the Trolless Chrome extension and activate it within Facebook, each account that is determined by Trolless to be suspect appears with a red exclamation mark. In a simple way, the platform provides a visual cue that is the converse of Facebook and Twitter’s “verified” blue checkmark icons. The identification strengthens civil society efforts to prevent disinformation, manipulation, distraction of users’ attention from relevant subjects, use of hate speech, and public denigration, especially in election campaigns when fake profiles get a boost.

Users can also report suspicious activity or material themselves through the Trolless platform – the Trolless team investigates these reports, using tools to verify if photos were taken from another source or manipulated, or if the activity of the suspect user is disinformation or hate speech, for example.

Once it launched, Trolless users began to report suspect profiles and pages, stolen identities, falsified images and manipulative information. Disinformation is rampant, with observers noting that trolls even stole the identity of an official anti-fake news platform, STOP FALS.

Moldova’s upcoming parliamentary election, originally scheduled for the fall, is contentious and will be watched closely, as Moldova is politically split between pro-Western and pro-Russian sides, and distrust runs deep among ruling and opposition parties. These elections are also introducing a new system: half of members of the parliament will be elected on party lists and the rest will be individuals voters can elect to represent their local interests. Getting unbiased information is very difficult for ordinary Moldovans, as the two major parties together control about 80% of the media, and TV channels have been found to give unequal access to political parties and candidates in elections.

Removing false information

Spinu said the Trolless platform presented to Facebook in January a list with hundreds of fake accounts suspected of supporting different political parties through disinformation.

A few weeks later, Nathaniel Gleicher, Head of Cybersecurity Policy at Facebook, announced Facebook’s removal of more than 100 accounts or pages. About 54,000 accounts followed at least one of the pages and around 1,300 accounts followed at least one of the Instagram accounts, Facebook said.

Some of the banned accounts were not fake, but real individuals pushing false information, and some of those real accounts belong to employees of the governing party. The government responded in a statement that more than 200,000 employees work in public institutions, and their individual behavior on the internet is not monitored: “These employees have different political options and opinions, and the state has the obligation to preserve the border between fighting the Fake News phenomenon and guaranteeing freedom of expression for citizens.”

According to Trolless, the most important weapon against disinformation is media literacy and civic involvement.

The Trolless team says that their intent is non-partisan, not funded by political parties or beholden to commercial interests. The project has been funded by grants provided by the Center for Independent Journalism, Deutsche Welle Akademie, and the MEDIA-M project, implemented by Internews with the financial support of USAID.

(Banner photo: View of the capital city Chisinau, Moldova. Credit: InspiredbyMaps)