By Jenae Barnes

In 2018, reporter Amar Guriro covered the impact of heatwaves on slum dwellers in Karachi, Pakistan. His story followed a severe 2015 heatwave in Karachi that killed an estimated 2,000 people, with temperatures as high as 49-degrees Celsius (120 degrees Fahrenheit). The extreme conditions caused dehydration, heat fatigue and heatstroke in the hundreds of slums across the city of nearly 15 million people.

Guriro wanted to explore in-depth how the heatwave continued to affect informally settled communities even years later and determine what was needed to prevent a re-occurrence.

Using support and funding from EJN, he produced “A Portrait of a Karachi Slum During a Heatwave,” in May 2018. The story revealed the human face of the 2015 heatwave and showed how even as government officials and aid agencies disputed the number of deaths, those living in the city’s slums were still being overlooked.

Guriro later shared his story in a WhatsApp journalism group chat, where it quickly started to gain attention. Within weeks, local TV channels contacted him seeking sources to interview, and a non-governmental organization reached out about a project to help cool down tin roofs in slums.

A few months later, he received a message from the office of the Chief Minister of Sindh, Pakistan’s second-largest province and home to Karachi.

Rasheed Channa, media consultant to the Chief Minister of Sindh, said he contacted Guriro to gather more information from his reporting. He explained that Guriro’s story had brought significant attention to an issue that had been ignored and that the provincial government and the Chief Minister of Sindh now planned to regulate slums to give land rights and authority to settlers in the slums.

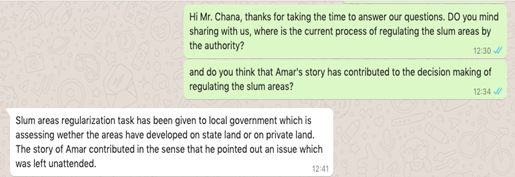

“The story of Amar contributed in the sense that he pointed out an issue that had been left unattended,” Channa told EJN via text message.

In messages exchanged with Channa by phone, Guriro detailed the lives of the slum dwellers he’d met during his reporting. He recounted the story of Samoda, a widow and mother of nine who lost two children in the 2015 heatwave in Machar Colony, one of Karachi’s biggest slums. From a population of approximately 700,000 people, over 1,200 died and more than 40,000 suffered from the extreme weather conditions.

Since the 2015 event, Karachi’s heatwaves have continually gotten worse due to a combination of climate change that is altering weather pattens and urban development that removes trees and other vegetation that keeps cities cool. The impact is felt the most in Karachi’s slum areas, locally known as “Katchi Abadies.” These are informal settlements that the government considers illegal because they lack land rights. As a result, settlers there often lack access to drinking water, electricity, or healthcare from the government.

Since Guriro’s story brought the lives of slum dwellers into the foreground in 2018, the provincial government has formally recognized the legal status of about 36 slum areas, in a city of over 500 such locales.

Channa shared this update about the process with EJN via WhatsApp in Sept. 2019:

Channa: Slum areas regularization task has been given to local government which is assessing whether the areas have developed on state land or on private land. The story of Amar contributed in the sense that he pointed out an issue which was left unattended.

If the settlers are on public land, the government asks them to pay a fee in return for rights to occupy the area and access government services, such as water, Channa said. The process has become more difficult, however, as more migrants have flooded into Karachi, many driven by climate change impacts. The Machar Colony is still in the process of being formalized as of Feb. 2021, Channa said.

Zulfiqar Kubhar, a Karachi-based journalist and member along with Guriro of the National Council of Environmental Journalists (NCEJ), credits Guriro’s reporting for bringing climate change to the attention of officials in high levels of the government.

Sensitizing the public to climate change was a joint effort from journalists that Kubhar said “forced governments to reconsider their policies.” And this led to some of the changes they’re seeing today, he added.

The road to environmental reporting

Guriro first connected with Internews during a media training on flood coverage following a super flood event in Pakistan in 2000. Guriro had covered environmental issues for few years prior to the training, but he said the relationship he build with EJN was pivotal.

“My time with EJN made me realize environmental journalism was important, and I had to continue with it,” he said.

Guriro and the other workshop participants like Kubhar later formed NCEJ, the first environmentally focused journalism organization of its kind in the country. Through the years, Guriro continued to participate in EJN fellowships and workshops, traveling from Nepal, to San Francisco, to Berlin to cover global environmental conferences.

Guriro now works as a staff reporter with the Independent Urdu and said the professional journalism skills he honed by working with EJN have allowed him to stay employed during a time of hardship for journalists in Pakistan and globally.

Since the heatwave story in 2018, Guriro has continued to write about slum dwelling communities, including a series on the impact of heatwaves on women in urban slums.

He also draws on his Indigenous heritage to create a personal tie to marginalized peoples.

In Pakistan, as elsewhere, Indigenous communities often feel the impacts of climate change more intensely because they often lack access to resources like healthcare, are usually more dependent on their environment, and tend to live in poorer communities. Guriro’s family has personally been impacted by the extreme weather conditions induced by climate change, and he said his experience is what drives him to cover environmental issues and their impacts on other marginalized communities.

“Climate change is in my genes,” he said.

(Banner photo: In the slums, those women who can’t afford to buy water, have to walk long distances in search of water, even during heatwaves. Credit Amar Guriro)