Read the Report

Before the COVID-19 pandemic stopped Zimbabwe in its tracks, the country faced severe economic challenges and had already seen devastating climate disasters. Repeated periods of extreme drought triggered food crises. Flooding and storm damage from Cyclone Idai (March 2019) devastated eastern parts of the country, wiping out crops, damaging infrastructure, and killing both people and livestock.

Those crises, coupled with acute shortages of foreign currency and rampant corruption, led to double-digit declines in agriculture, and electricity and water supply production. In 2019, the currency depreciated, and the annual inflation rate soared to 737%. Food prices increased 725%. Wages could not keep pace. Around 95 percent of people lived in the informal (and often subsistence) economy.

The advertising market, slim at an estimated $152 million when last reported in 2015, was largely captured by media organizations aligned with government interests and receiving state-funded advertising.

The pandemic also triggered a decline in human rights. Government critics were abducted and tortured. The police and security forces committed arbitrary arrests and other abuses, including assault and torture. Journalists were also under attack. Police used the pretext of lapsed credentials to arrest journalists.

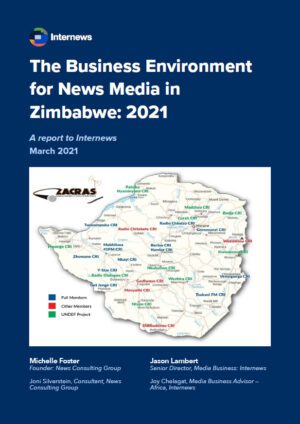

Amidst this, new laws regarding journalism and journalists were drafted (and one passed) repealing earlier ones. While the government claims that the new laws are less restrictive, in practice they have heavier penalties and severe restrictions, particularly regarding political reporting. The media market has expanded somewhat under these laws: the government issued new licenses for community and university radio stations which will expand reach of local news in local languages. However, the path forward for funding these new media channels remains unclear.

The cost to establish a broadcast television channel is prohibitive except to either well-heeled individuals or corporations. Media operators, understanding that access to broadcast channels is likely to remain beyond their reach, have instead turned to innovative digital channels using WhatsApp, bulk SMS, and social media to reach audiences on their cell phones. The digital broadcast conversion, under a 2015 deadline set by the ITU, has not yet been fully implemented. However, at some point, this process will be complete. It will free up large swaths of the broadcast spectrum and expand telecommunications and access to digital media; Zimbabwe’s news producers, already aggressively using digital platforms, will have the means to bypass traditional broadcast and print channels and directly reach wider audiences.