For the last decade, the residents of Fiji’s Narikoso village on Ono Island have watched the sea level rise and endanger their homes. The village is one of 40 the Fijian government has identified as being in need of relocation to higher ground due to the effects of climate change – but since 2011, when mitigation and adaptation efforts were first discussed by the government, they have still been waiting to move.

“We’ve had so many officials from government and NGOs come by and conduct assessments, but they go back and nothing else happens,” said Kelepi Saukitoga, Narikoso’s village spokesperson and the chairman of the village development committee.

Then, in September 2020, Fijian journalist Stanley Simpson was covering successful relocation efforts in another part of the country and learned about Narikoso from a source. When he discovered just how long the villagers had been waiting, he said he knew he had to visit.

“I contacted some of the villagers, and they started to tell us a story about how the situation had not been handled well from the beginning,” Simpson said in an interview with EJN. “There were good intentions by government officials, but if you don’t do it the right way, you can cause more harm than good.”

But travel to Narikoso is difficult and expensive. Simpson applied for an EJN story grant through our Asia-Pacific Project in 2020 and was awarded travel funds to make the trip later that year. He says the support was invaluable, allowing his team to take the time they needed and tell the story right, without rushing it.

“The grant was immensely helpful,” Simpson said, explaining that it came at a time when the Fiji economy was struggling. “The support and the partnership with EJN allowed us to be able to give time to the project.”

In order to get there, Simpson and a photographer had to take the inter-island ferry from Viti Levu, the main island. They slept on the deck for the night, next to the exhaust pipe, and then had to switch to another boat in order to reach Narikoso. When they finally arrived, Simpson said the villagers were incredibly welcoming, and they provided food and shelter for the journalists for three days.

“When I first met them, I could sense their frustration and passion. They really cared about the community. I said, ‘Look, I have to tell these people’s story’.”

Fijian journalist Stanley Simpson

Story spurs new action

After spending time in Narikoso and then taking another long boat journey back to the main island, Simpson published text and video stories about the situation in the village. He explored what went wrong – including a change in agency policy that limited the number of families that could be relocated, excavation work that further damaged the coastline and the many bureaucratic and funding delays.

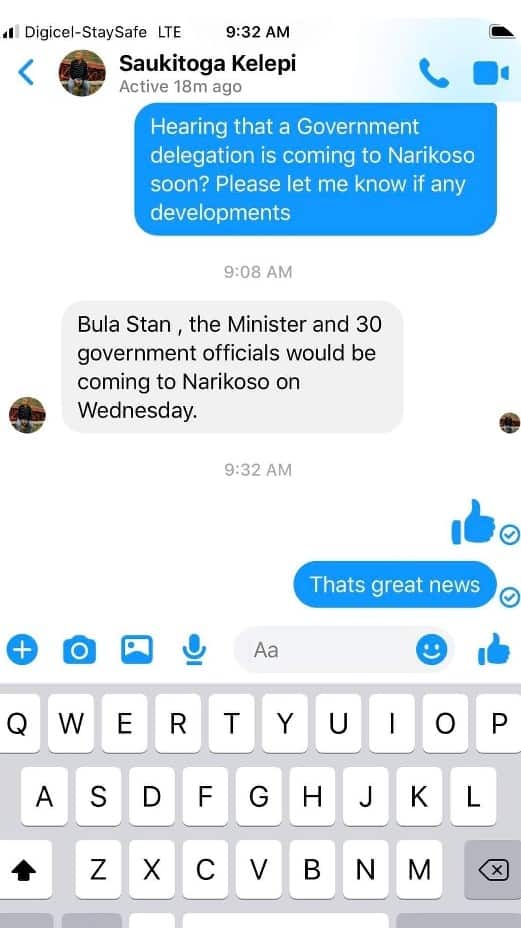

Simpson said his story appeared to get the government’s attention, spurring renewed action from Fiji’s National Disaster Management Office, the Minister of Maritime and Rural Development Inia Seruiratu and even Prime Minister Frank Bainimarama, who retweeted a post about the Narikoso community shortly after the story was published.

Finally, in November 2020, Bainimarama officially inaugurated Narikoso’s relocation area, spurring numerous news reports from the Fiji Sun, the Fiji Times and Fiji Village that further highlighted the challenges faced by the communities that called Narikoso home.

Compared to earlier news coverage, which Simpson says was almost nonexistent, the amount of attention Narikoso has received since he published his story has been remarkable. Although there is still much work to do, village spokesperson Saukitoga said after waiting 10 years, the stories Simpson produced made a real difference.

“Stanley’s story made the government move a lot quicker in getting us relocated,” Saukitoga said. “His story was done in September [2020] and by November, the prime minister came to open the relocation site. We are very grateful.”

Narikoso then and now

The residents’ predicament is far from resolved. Although the relocation site is now open, only a few households have been relocated so far. Those houses were in the ‘red zone,’ meaning they were the most affected by high tide and the rising sea.

Originally, the villagers reached a consensus to move the entire village — 27 households, two churches and a health center — together to higher ground. But the relocation agency decided later to only move those in the ‘red zone’ — about 7 households. Fracturing the village was an unintended consequence that has proven challenging.

In addition, when Fiji’s government brought military engineers to excavate and prepare the new village site, many villagers say mangroves were removed from the coastline as a result, even though mangroves are a crucial natural barrier against coastal erosion, and an important carbon sink. Both Narikoso’s residents and the owners of the land at the relocation site told Simpson they felt excluded from the government’s plans.

Besides the ever-growing threat of sea level rise, Narikoso and other villages in the Kadavu Island chain face other risks too: In 2016, Tropical Cyclone Harold damaged several houses at the site that were being built for the villagers’ relocation.

In 2015, an analyst was sent to the village to conduct a cost-benefit analysis. The resulting report, which Simpson highlighted in his article, said the government may have “jumped the gun” on some key parts of the relocation, and called on Fijian officials to enact relocation guidelines to prevent another Narikoso situation from happening elsewhere. Since then, the government has developed relocation guidelines, but their effectiveness has not been covered by the media yet.

As for Simpson, he’s interested to know whether these new guidelines will improve the relocation experiences for other villages. For his next project, he’s planning to tell those stories from Fijians across the country, evaluating whether the lessons from Narikoso were actually learned.

“The government has been quite strong and proactive in taking action on climate change and I am proud of that. But as journalists, we need to keep holding them accountable and pushing them to do better.”

Fijian journalist Stanley Simpson