Saba Rehman wanted to go to prison.

That might seem an odd wish in Pakistan. But Rehman had her reasons. The young photojournalist knew lockups in her country were generally out of bounds for any reporter, much less a woman. But she also had a hunch that inside prison walls, there were stories to be told.

“I am a local girl,” Rehman said she told authorities at Mardan Central Jail and regional leaders in three months of repeated pleas. “I am a Pashtun girl. My family lives here. My father lives here. My brothers. Let me in. Let me portray the lives of the women inside the prison walls. This is not just their story. It is our collective story. And I know how.”

The photos Rehman took inside the detention center last year, distributed in November by the BBC, broke new ground. She became the first Pakistani photographer, male or female, permitted inside one of the country’s prisons. She captured moving photos of women sentenced to death. And she used the opportunity to do what she is increasingly known for in her field – illuminate a little-seen and deeply misunderstood corner of her society.

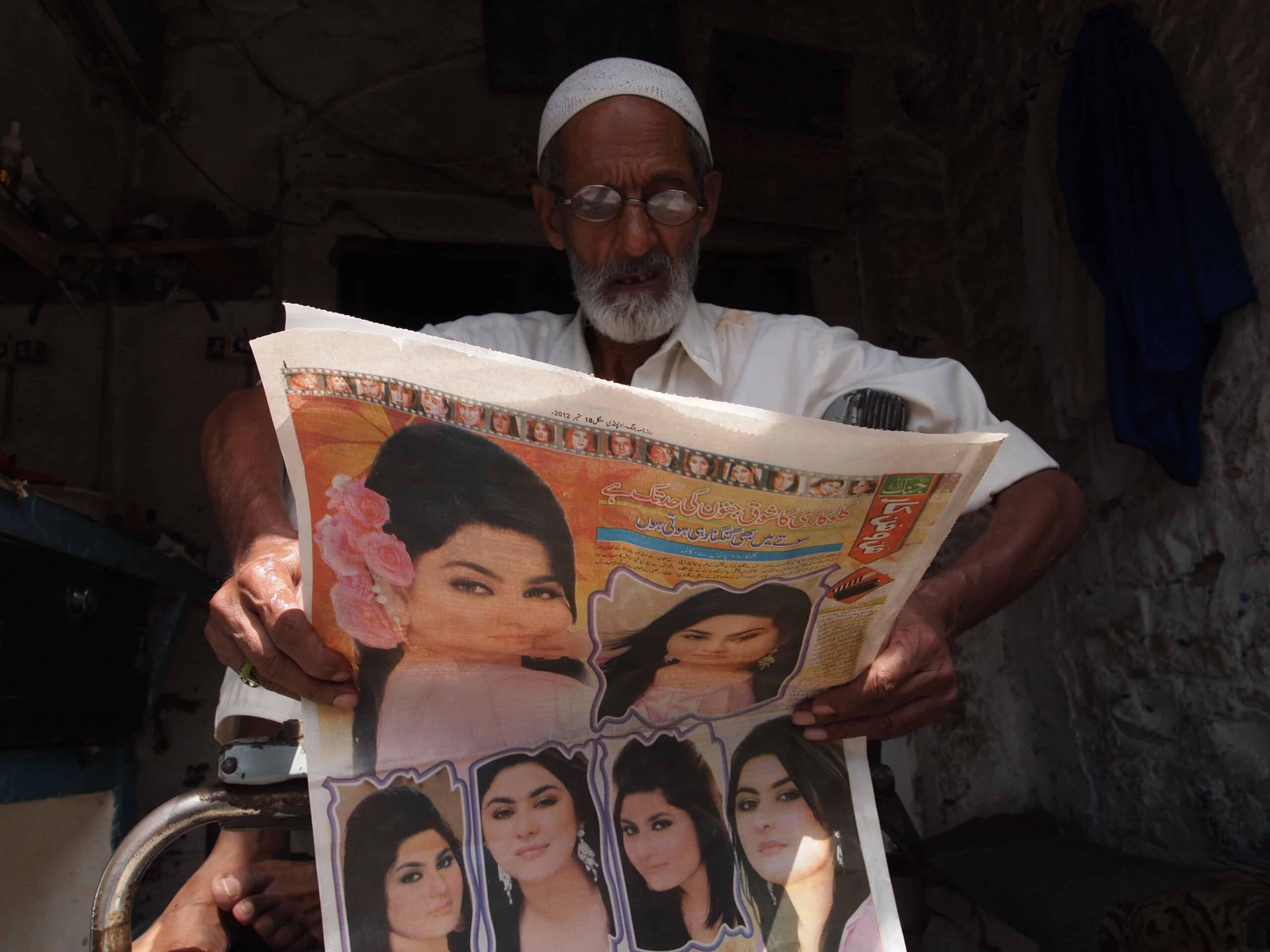

Rehman is an outlier in her region of northern Pakistan, the Pashtun belt of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, where federally administered tribal areas (FATA), recently merged into the province, have been wracked by poverty and unrest. Since 2012, when she was one of 17 Pakistani young people selected by Internews to attend an intensive photography training, conducted in partnership with National Geographic Photo Camp, Rehman has been getting herself and her camera into the most unlikely of places.

Rehman “has a tremendous eye for detail and a lovely eye to capture the emotions of the people whom she’s photographing,” said Kathy Gannon, Senior Correspondent for Afghanistan and Pakistan with the Associated Press, which has published Rehman’s work. “She is dogged. She is thoughtful. I admire her willingness to go just about anywhere. She gets stories that others haven’t gotten.”

Rehman “has a tremendous eye for detail and a lovely eye to capture the emotions of the people whom she’s photographing,” said Kathy Gannon, Senior Correspondent for Afghanistan and Pakistan with the Associated Press, which has published Rehman’s work. “She is dogged. She is thoughtful. I admire her willingness to go just about anywhere. She gets stories that others haven’t gotten.”

At just 30 years old, Rehman doesn’t cover the violence and politics that are all most people in the United States know of Pakistan. She is on a mission to broaden the narrative of her region. Wielding a single camera and a bag full of lenses and equipment she received back at that camp six years ago and that she cleans and guards zealously, she contributes to AP, the BBC, Al Jazeera, Arab News and NextTV.

Last year, Rehman was one of 22 photographers named to the prestigious Women Photograph mentorship program. The program, created in 2017, pairs leading photographers and photo editors from outlets like NPR, National Geographic and TIME each year with 22 early-career photojournalists from around the world. More than 800 applied.

Rehman is making her mark chronicling the changes in her society that have shaped her young life. From behind the lens of her camera, and sometimes in the role of reporter as well, she tells the stories of both the revolutionary and the marginalized.

This month, she photographed and reported a story of a student who writes with her foot. Her hands were amputated after they were struck with a live wire.

And last July, Rehman published a series of photos of a transgender woman running for a seat in Pakistan’s provincial assembly, one of 11 transgender candidates running since the country passed a law bolstering their rights two months earlier.

“When I go to a place, I sit with people and I talk about their families,” Rehman said. “I take tea with them, and only when they feel comfortable do I start taking pictures.”

Rehman faces significant challenges as a woman with a camera. A petite woman proud of her modern dress and bold pixie haircut, Rehman said she is careful to cover her head and face when necessary and to dress to blend in when she is working in traditional areas. While she prefers to work alone, she often is forced to rely on her male driver or her husband, a local broadcast journalist, to accompany her on assignments small and large.

“Talk about persistence and level of difficulty. In the place she’s working, she is doing things that are not easy to do anywhere,” said Kirsten Elstner, a veteran photographer who has directed National Geographic’s more than 90 Photo Camps in over 20 countries since 2003, and who mentors Rehman.

“She’s willing to try things that aren’t the norm for a woman in her region.”

What is the norm for women is Pakistan is changing. While many live deeply traditional lives, increasingly young people are encouraged to pursue medicine, teaching, engineering and law, regardless of gender.

Rehman is the beneficiary of some of those shifting norms. She grew up in the small city of Tarbela, where her father worked on a major dam project as an engineer for Pakistan’s Water and Power Development Authority. In Tarbela, unlike in some areas of the country, educating girls is the rule.

Rehman got a master’s degree in journalism from Peshawar University, But her path since has been far from easy. Out of around 15 women who graduated with her, Rehman says she is the only one still pursuing the profession.

Instrumental, for her, was not only that first Photo Camp, but the opportunity Internews and USAID gave her the next year to come to Washington, D.C. to study photography again. There she roamed the city with other photographers at a National Geographic Photo Camp Master Class, and saw her work displayed in a group exhibit at the U.S. Institute of Peace.

“I want to do each and every thing and if a boy can do so, why not I?” Rehman said. “I believe there is no such thing as a male and female photojournalist. There is only a photojournalist.”

Since 2010, Internews has partnered in 11 countries with National Geographic Photo Camp, which helps young people from underserved communities, including at-risk and refugee teens, learn how to use photography to tell their own stories, explore the world around them, and develop deep connections with others. Photo Camp Pakistan, in 2012, was supported by USAID.

(Banner photo: a young girl in rural Pakistan pretends to make a dam. Credit: Saba Rehman)