By Lukasz Krol

A note of Introduction

In theory, Central European journalists should have excellent digital security. Many of them come from countries where surveillance was the norm just a few decades ago and should therefore be aware of its risks. They usually have brilliant foreign language skills as well and can access a myriad of security guides authored by organizations all over the world. Reality, however, has proven to be more complicated. Central European journalists often lack the digital security knowledge that their peers in other countries might have. Not only this, but they often struggle to define their security needs as well.

In order to remedy this gap, I organized interviews with around a dozen journalists, media, and security experts from across Central Europe. In addition, I also read through much of the existing academic and nonprofit research on journalist security. In general, I looked through English-language content, as there have been next to no attempts to translate major digital security guides into other languages used in Central Europe. Most of those materials I ended up studying, while valuable, were also incredibly US-centric. Localization work is clearly necessary.

One of the main comments I received, both in the interviews and in the desk research, is that many security resources and trainings feel rather generic than targeted towards journalists. Still, many journalists see their work as far more than a profession: it is a calling, a search for truth, a culture, and an ethos. As such, the degree to which journalists’ professional self-image differs from other at-risk groups (human rights defenders, political campaigns) impacts their threat models as well.

This research—and the whole Journalist Security Fellowship it underpins—therefore has several goals in mind. First of all, it aims to explicitly define some of the security concerns Central European journalists might have. Secondly, it attempts to understand why journalists from the region have rarely been receptive to existing security guides and trainings. Finally, it sets out to define training priorities for regional journalists, which will set the tone for later trainings and materials created as part of the Fellowship.

Some of the main trends we identified

Memories of surveillance differ

There have been few notable efforts to localize digital security training materials into Central European languages. As such, local journalists must frequently rely on English language ones. Most of those which reflect a very American perspective, which has frequently been informed by the Snowden-National Security Agency (NSA) revelations. Though countless other domestic and foreign bodies engage in surveillance, the NSA leads provided US-based journalists with a clearly defined threat, and one that could be mitigated through tools such as Tor or Signal.

However, these American-centric threats and solutions are not necessarily applicable for journalists in Central Europe. Central Europe’s authoritarian legacy has made surveillance vague, ever-present, and pervasive. You could be surveilled by the secret services, the armed forces, the police, employers, or your neighbors. This historical context, which affects people’s thinking, often leads to a general sense of security nihilism.

There’s a low level of digital security knowledge in general

There are several reasons for the aforementioned nihilism. First is a result of limited awareness surrounding the issue. Most of the journalists I spoke to attended few, if any, digital security trainings. Not many organizations offer such trainings and those which do rarely advertise them. Most newsrooms hardly prioritize digital security and, as such, rarely allocate funding or attention to them. This also makes it hard for individual journalists to upskill themselves, especially since good security requires a wider community and organizational effort.

Classes by Google’s News Initiative often taught journalists how they could use the company’s products—such as Maps—to strengthen their reporting but did little to spread awareness of services such as Google’s Advanced Protection Program, which is designed to lock down the email and cloud accounts of at-risk users. In part, this is due to a low demand from journalists themselves, who rarely consider security a key training priority. Many factors help explain this, including prior ill-suited security trainings and a sense that most journalists simply do not work on sufficiently sensitive or important topics to become a target of digital attacks.

Some of the interviewed journalists also misestimated their level of security knowledge. One interviewee was a proficient user of Signal, understood the risks of communicating via unencrypted channels, and regularly checked haveibeenpwned for leaked passwords, but felt frustrated that she didn’t understand the basics of digital security. She certainly had a solid understanding of digital security, but also seemed overwhelmed by the perceived vastness of the field. Other journalists would hardly stop to think about risks, or consider themselves not a prime target for hacking. They would not even implement security mechanisms recommended for low-risk groups, such as basic two-factor authentication or unique passwords.

Another perception, found both in the readings I conducted and in conversations with most journalists, is that security considerations largely depend on a journalist’s beat. The thinking goes that journalists dealing with fields like sports, arts, or mainstream business have little to worry about, in contrast to national security or investigative reporters. Few of the interviewed journalists seriously considered a scenario in which the hacking of a journalist with a less sensitive beat would grant access to the whole organization’s cloud accounts. Security tends to be flattened to the level of an individual, ignoring its community aspects. This is due to a variety of factors, including the ‘competitive-collaborative environment’ in which journalists often operate. They compete for bylines and scoops, while simultaneously collaborating on big stories and investigations. Journalists also often develop their own workflows, security mechanisms, and ways of cooperating with sources. Few security guides offer guidance on organizational security, either, and almost all of them are addressed to individuals, rather than bigger teams.

There’s a perception that security slows down, rather than aids, reporting

Journalists often work under tight deadlines and rarely have the luxury of time for self-study or to tweak their workflows. As one interviewee explained, “I’m a busy parent, and a journalist. So, I have to choose between cooking and learning about security, and cooking always wins.”

The journalists I spoke to often expressed a great wish to learn more about security, but also felt that most existing trainings and guides hardly aligned with their priorities. This was due to two reasons. Digital security guides rarely focus on a single journalistic user journey or workflow (for example, ‘securely contacting a source’ or ‘viewing an untrusted document’), and it sometimes felt like journalists would need to modify their workflows towards digital security priorities, rather than the other way around. Not only this, but existing trainings rarely focused on usability, or overemphasized tools or training techniques at the cost of operational advice. In short, the trainings hardly offered ways in which journalists could easily integrate new security behaviors into their existing day-to-day activities.

Interviewees suggested that Internews organize trainings that provide highly practical advice (such as five ways to secure your Facebook account) and simplify journalistic work (for example, how they can look up persons of interest in social media without being tracked).

People wanted to get better at ‘digital’ as a whole

In many journalists’ mental models, confidently navigating digital security had less to do with security and more to do with understanding the ‘digital’ world as a whole. Journalists want to better understand what digital tools and tactics are at their disposal, including those related to data investigations and open source research. Any lack of confidence that they might have with regards to digital security concepts is often related to general issues with intuitively grasping the digital world.

In part, this happens because media organizations’ IT teams rarely had expertise in issues like threat modelling or in-depth knowledge of the pros and cons of different encrypted messengers. Their main role focuses on keeping websites, accounts, and computers up online. The newsroom technologist, or someone who easily straddles the worlds of technology and the media is a rare breed in many Western publications, and nearly non-existent in Central European ones. Limited media budgets, and high IT salaries, are partially to blame for this. Not only this, but when Central European editors seek out the help of programmers or technologists, they often do to solve a defined problem (such as creating a new data visualization) rather than to get a technical perspective on an undefined problem (for example, getting troves of data which must be sorted through). All of this leads to a situation in which Central European journalists rarely have what they themselves would consider an intuitive understanding of the digital world as a whole—and security trainers and guides must also keep this in mind.

Harassment seems inevitable and takes on many forms

Journalists are at particular risk of harassment because of their public-facing nature. With a few notable exceptions, most publications prominently display the names of authors in bylines. While representatives of other professions might use pseudonyms or other means to hide their identities, journalists rarely have that luxury. Their personal brand remains one of their most valuable professional assets.

Harassment is a major problem for journalists, and often aims to discourage a journalist from pursuing a story—or to get them to drop out of journalism altogether. In some cases, the journalists interviewed for this study implied that harassment was so commonplace that they had simply become desensitized to it or considered it an unsolvable problem. Tools such as Twitter blocklists, which are rising in prominence in the anglosphere, were not really discussed or used by the journalists I spoke with.

Often, harassment would also take on a legal form, with powerful actors threatening lawsuits against journalists and media outlets to drain their resources and discourage them from pursuing investigations. Here, technology might be of help.

There are notable exceptions to Central Europe’s security nihilism

The security champion is an individual or group who deeply understands security, and shares this knowledge with the environment around them. Our conversations have shown that this dynamic exists among Central European journalists as well, many of whom have a friend, colleague, or organization whom they rely on for security advice. In Romania, the investigative RISE Project has emerged as one such security champion: many of the journalists I spoke to noted that they rarely considered digital security before starting work with them. The security champion dynamic is a powerful one, and only further justifies the focus of our Internews fellowship on training up a group of media-adjacent security experts who will then go on to advise and help their communities.

Key training recommendations

Make sure your trainings fit your target audience

A targeted security training is an effective security training, as both our interviews and Kristin Berdan’s brilliant study of online digital security guides confirmed. Having analyzed around 33 security guides for journalists (which contained around 300 pieces of advice in total), Berdan concluded that most offered generic security advice, with few looking at issues such as source protection or harassment which journalists in particular might be facing. Most guides also focused on tool recommendations (for example, Signal or Tor), and hardly included operational practices (such as travel, border crossings, or receiving documents). Trainings need to do better than that; they should be hyper-targeted, both towards the needs of journalists as a whole and towards the specific threats that journalists in Central Europe might face.

Build trainings and threat models on real-life case studies

The most effective doctors, fitness trainers, or dieticians are often those who do not just give out excellent advice, but also package it in ways that encourages the recipient to follow it. We must do the same when offering digital security advice. One of the best ways of doing so is by building our trainings on case studies of past attacks, such as the phishing attack on the ProtonMail accounts of those who wrote pieces critical of the Russian government, or governments which used Pegasus-like attacks. Such examples demonstrate that breaches are not a faraway concern, but could happen to anyone. They also help with building realistic threat models. While journalists I spoke with mentioned a myriad of security risks, including break-ins to cloud accounts or mobile phone tracking, they struggled with estimating the probability and impact of such risks. Threat models that are built on real-life case studies should help in this regard.

Frame digital security as something that will help journalists become better at their job

The best security advice will directly assist journalists in their work and investigation—for example by allowing them to stay anonymous when researching companies or helping gain the confidence of sources by ensuring that they will not easily be surveilled or exposed. Some of the journalists I spoke to had plenty of questions on whether they should be contacting sources from burner phones or anonymous numbers: crucial operational details that many security guides overlooked.

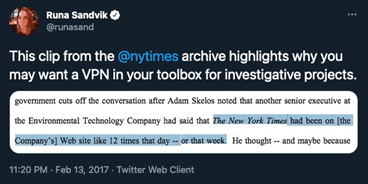

The above Tweet, from Runa Sandvik, describes how the New York Times accidentally alerted one of the subjects of its investigation by failing to use a VPN and exposing its IP addresses.

Focus on usability, productivity, and workflows

While journalists would like to become more secure, they also struggle to figure out how to do so while remaining productive. The most effective trainers should not just advise on tools and procedures but should also help individual journalists develop simple workflows (such as automated backups, easy password management, or custom-made setups for opening potentially dangerous documents). Journalists will be far more receptive to digital security training whose solutions save rather than take up time.

A security trainer cannot be solely seen as someone who constantly says ‘no’ to things. If users disagree with security advice or if it excessively complicates their lives, they are likely to just ignore said advice while hiding this fact from the security team.

The digital security trainer could also be a guide to the wider digital world

A digital security guide is usually an expert in the ‘security’ sphere rather than in the wider digital world. They must understand the basics of encryption and operational security, but do not necessarily also have a deep background in topics such as open source research or investigative toolkits and techniques. Still, since many journalists place digital security as part of a wider ‘digital’ rather than merely ‘security’ mental model, a trainer might become even more persuasive if they are also ready to share some advice and toolkits such as Tactical Tech’s Exposing the Invisible.

Dont forget about organizational security

Security is only as strong as the weakest link. If a journalist’s notes or drafts are shared on a shared cloud space or emailed to several people, then a successful break-in only needs to target a single account with access to such data. This issue, along with wider notions of organizational security, has been rarely addressed by small media organizations or digital security guides. Even organizations that keenly embrace tools such as password managers, secure messaging, and VPNs will often forget about basic procedures for onboarding and offboarding team members, and might for example forget to revoke access to the shared Google Drive or social media accounts once somebody leaves. A good trainer should work closely with an organization to develop clear organizational security checklists and procedures.

Help journalists balance public personas with safety and privacy

Many journalists have trouble balancing a public persona with their own safety and privacy. They wanted to learn how they could share some personal information, for example if they traveled to a different city to do reporting, without leaking information such as location data or car license plate pictures that could be used by a would-be harasser. Basic operational practices like this seem like the most necessary short-term intervention, rather than complex social media filtering tools.

Consider the ways in which technology also addresses legal questions

Tools and processes such as SecureDrop or disappearing messages are sometimes seen as not just technical countermeasures but also legal ones. Organizations cannot be compelled to give access to data if they are physically incapable of accessing it. By making it impossible to surveil communications, such tools also do away with legal cases related to data requests. Such countermeasures have rarely been tested in court, and even less so in Central Europe. In countries such as Poland, journalists’ right to privacy is enshrined in law and police forces are unlikely to openly seize media institutions’ data; covert surveillance by intelligence services is a far more probable scenario. A digital security trainer does not need to be an expert on every legal issue that the communities with which they work might face, but should appreciate and actively ask questions about this dimension as well, and be ready to offer counsel on possible technical countermeasures.

Acknowledge that we are preparing for the unknown, not the known

Whenever we use tools such as models, attacker personas, and archetypes to model our security, we must remember that they only offer certain templates, rather than demonstrating every attack we might ever face. It’s crucial to teach journalists to respond to different scenarios—including those that differ from what they were taught in their initial trainings. In the months and years to come, phishing scams and social engineering attacks could evolve in ways we never foresaw. Our trainings must acknowledge that and embrace a healthy level of vigilance and flexibility.

How technological solutions can do away with legal questions

SecureDrop is not the only technical countermeasure that can also offer legal protection. Several companies seem to pursue such a strategy, even if they do not openly frame it as such. After the FBI requested that Apple unlocks an iPhone for them, the manufacturer redesigned future versions of their flagship product as to unable to do so even if they wanted to. Signal similarly refuses to collect metadata while building technical systems that would make it impossible for them to do so.

List of guides and articles that were analyzed

- An Evaluation of Online Security Guides for Journalists, Kristin Bedran

- “Security by Obscurity”: Journalists’ Mental Models of Information Security, Susan E. McGregor and Elizabeth Anne Watkins

- The Information Security Cultures of Journalism, Masashi Crete-Nishihata et al.

- Breaking Through the Ambivalence: Journalistic Responses to Information Security Technologies, Jennifer R. Henrichsen

- Creative and Set in Their Ways: Challenges of Security Sensemaking in Newsrooms, Elizabeth Anne Watkins, et al.

- The Role of Corporate and Government Surveillance in Shifting Journalistic Information Security Practices, Martin L. Shelton

- Would You Slack That?: The Impact of Security and Privacy on Cooperative Newsroom Work, Susan E. McGregor, Elizabeth Anne Watkins, Kelly Caine

- The Rise of the Security Champion: Beta-Testing Newsroom Security Cultures, Jennifer R. Henrichsen

- Protecting Journalists’ Sources Without a Shield: Four Proposals, Anthony L. Fargo

- Ties That Bind: Organisational Security for Civil Society, The Engine Room

- Exposing the Invisible, Tactical Tech