Following the earlier contributions to this blog series, which provided an overview of the six GNI-Internews fellows’ research projects, in this collection, fellows document their work over the last few months.

This post was originally published on Medium

When we started this research at Hiperderecho, we had some idea of what we were going to find. As we said in our first blog post in July, although Peru is not currently a country known for being hostile to human rights, there are certain practices that are far from being respectful of fundamental liberties, especially those that are adopted to increase security. However, what we finally found has made us reassess the magnitude of the problem. Spoiler alert: it is bad news.

When we think of Internet censorship, the first thing that comes to mind is Internet shutdowns and blockages. A government decides that there is information that they don’t want to circulate among the population and orders to block it. To do this, they request that Internet providers block specific IP addresses or URLs. If the issue is more serious, they block the addresses in the domain name system (DNS), which denies access to entire platforms. In authoritarian regimes, where the government has control over the entire local Internet infrastructure, blocking sites or disrupting access in specific regions comes as easy as pressing a button.

However, not all blockages are illegal or undesirable. There is consensus in the world that certain content simply should not be on the Internet (or anywhere else), such as child sexual abuse imagery, illegal trade of weapons, and terrorist threats. But there are also other cases where it is less clear whether the content is totally undesirable. The most common examples are content that infringes copyright, libel, etc. For the latter, it is most common to see specific rules in each country that require complainants to go through a process where a judge or an impartial third party intervenes to decide, case by case, what is appropriate.

In Peru the system works that way with two exceptions. The most recent is a Supreme Decree of the Ministry of Transport and Communications (MTC) that gives this entity the power to request the blocking of Internet sites that promote passenger transportation services carried out by motorbikes. Another one is the ability of the National Defense Institute for Competition and Protection of Intellectual Property (Indecopi), an administrative entity in charge of intellectual property and competition enforcement in the country, to request the blocking of sites that infringe copyright. We consider that both are not very suitable mechanisms to legally block content on the Internet. As part of this way of thinking, we decided to compile a list of blocked sites and apps based on these exceptions, to show the public that this is real issue and should be of concern moving forwards.

The list that we presented at the end of our research contains 26 URLs that have been blocked at some point in the country. We found this information through a) requests for access to public information, which public entities are obliged to answer; b) media and the institutions’ press releases; and, c) reports of compliance with the net neutrality of the companies providing Internet access. Due to the inherent limitations of these sources, the list is not comprehensive, but it is representative of everything that has been blocked following these exceptions in Peru in recent years.

What’s on the list? Mainly football and music streaming websites, which have been accused of infringing copyright. In most cases, the blocks occurred between 2018 and 2019 and have currently been lifted or the sites no longer exist. In most cases, the blocking was ordered by Indecopi, at the request of those who considered themselves affected by the content. This last procedure is laughably simple: The affected entity need only send a letter to Indecopi requesting the blocking of the site as a “preventive” measure (preliminary injunction), to avoid being harmed during the administrative process in which Indecopi will examine whether their claim is fair or not.

Does that mean everything is okay? Not at all. Possibly what the list shows does not concern anyone. It is even possible that there are those who are in favor of this type of blockage. Does piracy not affect authors? Isn’t it dangerous for motorcycles to offer taxi services that are not regulated? After our initial findings, we realized something else about these blockages. They have all been achieved through ad hoc mechanisms. In the case of Indecopi, this entity has creatively interpreted its powers and concludes that in cases of copyright infringement, it can demand these measures. In the case of the MTC, they directly produced the norm that gives them these powers.

In other words, these two exceptions have been created in a way where they do not need to ask for permission. It could be said that they assume this “heavy burden” for the good of all citizens and that if this is the case, it is because nobody wants to take this responsibility. The truth is that both entities seem very proud to have these powers to block the Internet. On multiple occasions they have made public statements about it. For example, Indecopi stated in a press release that “they achived the block of Roja Directa”.

Right now the blocked sites might consist of pirated football and music streamers, but given the ease by which the process can be initiated, it is not far-fetched that these ad hoc mechanisms could one day serve to block any other content. It started with Indecopi, using its extended powers to block website that infringe copyright, but seeking this example the MTC proceeded to create it own regulation to do the same. It is possible that other ministries might want to follow the MTC’s actions in the future. The problem is the mechanism. Currently there are two blocking mechanisms in place that belong to entities that are not obliged to keep reports of what they order to block and are not subject to any control or oversight process. To prove this, we have started a list through multiple access to information requests.

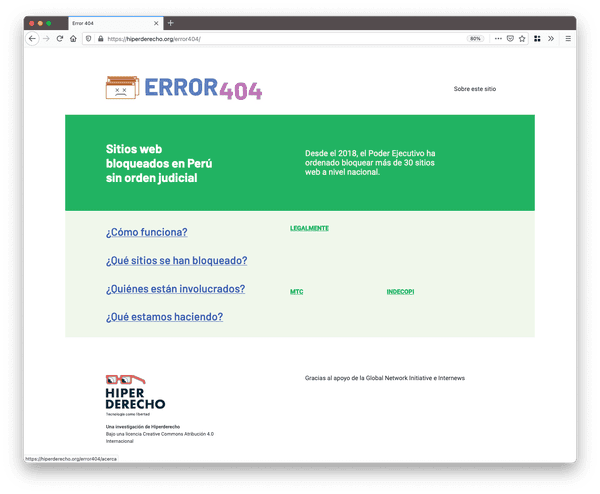

Thanks to the generous contribution of Internews and the Global Network Initiative through the GNI-Internews Fellowship, we have built a microsite where you can find the list of blocked sites and more information about the how, when, and why of these blockages in Peru., The idea is not only to look at the list for what it is, but to question if we really want the government to have mechanisms that give it so much power over what we do or do not see on the Internet. We are facing not only silent censorship, but also one promoted loudly by its advocates (Indecopi, MTC). This must stop. We need regulation that respects human rights and is necessary and proportionate. We also need transparency. Until that, we keep vigilant.