Climate change may be a hot topic at the moment, but it’s also one that leaves audiences prone to burnout. How could it not be when headlines such as “Climate Change Threatens the World’s Food Supply” or “Thanks to Climate Change, Parts of the Arctic are on Fire,” report apocalyptic scenarios that seem insurmountable?

Is the media to blame? Rather than telling stories about the impacts of a changing climate that strike fear and paralysis in readers, how can we highlight ways that people around the world are responding to these problems?

Covering solutions is one answer, and it was the motivating force behind a recent workshop hosted by Internews’ Earth Journalism Network and the Solutions Journalism Network.

What We Know About Climate Change

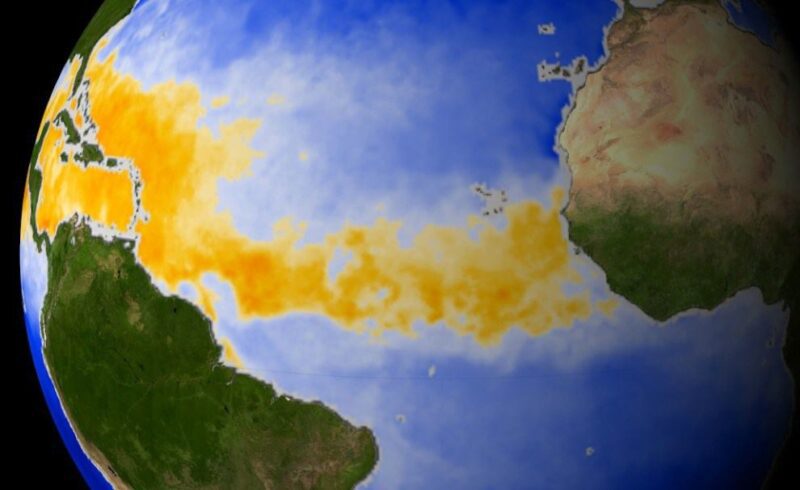

The planet is warming, according to broad scientific consensus, and that means really bad things: greater heat waves, melting glaciers and with it sea-level rise, increasingly intense wildfires, dying reefs due to bleaching and ocean acidification. The impacts are making food harder to grow, displacing human communities and destroying wildlife habitats, contaminating water sources and raising the threat of pests and disease.

What’s worse, that warming is accelerating. This July was the hottest month ever recorded, according to the World Meteorological Organization, and 16 of the 17 warmest years on record have occurred since 2001.

The Challenge

That all sounds bad, and media coverage of these threats hasn’t really been commensurate.

In part, that’s because media as an industry is struggling, which means fewer reporters to cover the “climate beat” and fewer resources to seek out solutions. Newsrooms also still lack diversity, which reduces the variety of coverage and content, and means that the communities hardest hit by climate change often don’t get covered. And solutions, well, they’re often an afterthought.

A 2018 study by Media Matters of climate change coverage by the top US television news stations showed that only 1 in 5 segments even mentioned solutions. The effects of climate change on public health and national security received almost no attention.

Print media coverage of climate change has slowly increased, peaking around certain events, like hurricanes or global climate conferences, but a recent study from the University of Kansas shows that coverage alone isn’t enough: The way media frame climate change also matters.

“Not only can framing have an impact on how an issue is perceived but on whether and how policy is made on the issue,” said Hong Vu, the lead author of the study, which found that media in richer countries tend to frame climate change as a political/policy issue, while poorer countries frame it as a global one that the world needs to tackle.

News audiences, meanwhile, are starting to pay attention. And Americans generally are concerned about the problem – though less concerned than they are about river pollution, according to a recent Gallup poll. (See: Climate change being felt in Kentucky).

But it’s hard to get people to take action on something that seems far in the future or, worse, unsolvable. In many places, people don’t want to accept that their lives need to change to tackle the problem, while in places being hit the hardest, people often know the climate is changing but don’t know why or what to do about it (See: Why climate change is so hard to tackle).

In this On The Media episode, David Corn, Washington bureau chief for Mother Jones, talks about the psychological effects of climate change on those who study it. Corn wrote a cover story in July called “It’s the End of the World as they Know It.”

That’s Where Solutions-Focused Journalism Comes In

The “if it bleeds, it leads” journalism mentality has led to audiences—especially young ones—tuning out. The recent Reuters Digital News Report found that news negativity was the top reason audiences avoided the news. Rather than reinforce this news fatigue, solutions journalism focuses on shifting the balance by promoting forward-looking, rigorous coverage of responses to social problems and their associated results.

And it’s why a focus on solutions is often a better way to cover a topic as seemingly intractable as climate change. In fact, climate change is perhaps the No. 1 issue on which the media has the opportunity to shift the narrative from the problems to what needs to – and can – be done about them. (See: Shaming people into fighting climate change won’t work, says scientist)

So What Is It?

Successful solutions-focused climate change stories often look at local knowledge and community cohesion, movements, quirky innovations, cross-border lessons learned, traditional knowledge revival or new technologies borne from old.

Stories about mitigation – such as tree planting and forest preservation, switching from fossil fuels to renewable energy or carbon capture schemes – and adaptation – building coastal defenses to protect communities from rising seas, switching to drought- or flood-resistant seeds and crops – are some examples.

Some Takeaways When Covering Climate from a Solutions Lens

- Don’t make people look like victims or heroes. Do give them agency.

- Don’t promote silver bullets or one-size fits all solutions. There is no one solution/answer to the climate crisis.

- Don’t avoid other factors. “Natural” disasters, such as wildfires, are partly caused by drought and rising temperatures but also by development decisions, such as where and how residences are built, policies, etc.

- Look at what’s working, even if it’s not an ideal solution (See: “Migrants Face Changing Climate”). The climate crisis is new territory, so sometimes stories will be more about progress than proven solutions. What matters is that the solution is more than just a proposal and that the reporting is just as robust.

- Don’t overstate the role of climate change. Remember: Individual weather events are difficult to link to climate change.

- Distinguishing between local vs. global causes. Look at how governments monitor and plan for droughts and floods or how different water uses (to irrigate crops for the export market) can have local impacts.

- Avoid activism by focusing on an approach, not an organization, and including other views and perspectives.

- Avoid false balance. There is almost overwhelming consensus among scientists on how climate-warming trends over the last century are linked to human activity. Trying to balance that consensus with views from climate deniers or others who disagree with scientific findings risks misleading readers.

- Use data! Ground lived experiences in research and vice versa.

- Start with a local example of action and then tie that into a broader trend or issue. Is what’s happening in one place a model for somewhere else?

- And … don’t leave solutions to the end!

How To Make Climate Change Stories Compelling

- Use different angles, sources, desks, beats, editors

- Connect stories to people, places, wildlife; look at impacts on food, health, gardening, travel, money (things people care about and are familiar with)

- Use anecdotes + data, not jargon

- Use polls, investigative reports, graphics, photos, new media

- Explain probabilities, levels of confidence. Look at future projections but show how those scenarios can start to be addressed now.

- Good practices (adaptive measures) have taken on new urgency and move the conversation forward.

- Tell diverse stories. Climate change will impact different communities in different ways and there may be things similar communities can learn from one another. Show the range of people affected so it’s not just an ‘Us’ vs ‘Them’ story.

Questions to Consider

- Is the solution scalable and can it apply somewhere else? With what effect?

- What are its barriers to replication?

- What evidence is there to show that the solution is working? In what ways is it not and how do we know?

- What do researchers say? What do numbers show?

- Who are the critics and what do they say?

- What are the impacts? Has a certain scheme or technology helped reduce greenhouse gas emissions, for example?

- What are the shortcomings to this response?

- Where did this idea come from?

- What metrics matter when it comes to measuring success?

- And finally, know your audience. What are they concerned about? What do they already know? Is climate change a divisive issue and if so, how can you talk about it without alienating people?

(Banner image: Storms and Climate Change – Geology: U.S. National Park Service)