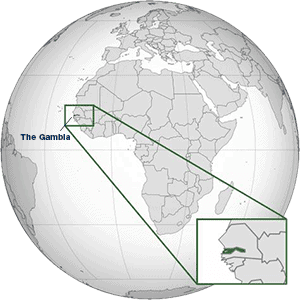

In 2017, when Alieu first started working on digital rights, The Gambia was ruled by dictator. Any criticism of the government, online or offline, was punishable with imprisonment, and in the run-up to the 2017 election, the internet was totally shut down.

In 2017, when Alieu first started working on digital rights, The Gambia was ruled by dictator. Any criticism of the government, online or offline, was punishable with imprisonment, and in the run-up to the 2017 election, the internet was totally shut down.

Alieu and his team were at risk because they were vocal and visible online, even though they were advocating for digital rights, rather than directly criticising any government official.

But Alieu says that this was an important time:

“We had to start the conversation about digital rights, and get people involved. There was no specific law at that time, but people were aware that the government was controlling what was being said, so they wanted to know more about it.”

Since the removal of the dictator in 2017, Alieu and his team have seized the opportunity to move forward with the new government.

At the time of writing, the government is carrying out a review of the entire Gambian Constitution, consulting civil society organisations like Give1 to ensure that the new Constitution reflects the rights, needs and priorities of the Gambian people.

Give1 used its Pioneer funding to expand the conversation around digital rights, and to help the government to understand the issue.

As Alieu explains, “The internet is very important in The Gambia. The new President boasted that social media is one of the reasons he was elected. And every single family in the country has WhatsApp. That’s all the government are thinking about – they’re not seeing the bigger picture.”

Give1 organised meetings and conferences to help government officials and civil society organisations (CSOs) understand just how critical the internet is to The Gambia.

Alieu and his team researched topics that they felt politicians would care about, and presented their case using research from the World Bank, private investors and other trusted bodies. For example:

The Gambia now has effective systems for disease surveillance, monitoring and reporting, which are already improving treatment for malaria, cholera and other preventable diseases in rural areas. All of these systems are online.

Remittances from the diaspora account for around 20% of the Gambian GDP. The vast majority of these transfers are made digitally.

The government met with tech companies in the USA, who were considering investing in The Gambia. But these companies said that they would not invest unless the government could guarantee that there would be no shutdowns.

At the same time, Give1 held a national consultative digital rights forum, which brought together over 70 CSOs, academics and policy makers.

This enabled the team to hone their message, and to bring very specific proposals to the Constitutional Review.

“We are focusing on the right to freedom of speech and assembly online; the right to privacy; protection from mass surveillance; and accessibility,” says Alieu.

“This review is a once-in-a-generation opportunity to create legislation that protects and upholds the digital rights of the Gambian people. We have to get this right for our country.”

More Case Studies:

Togo | Bolivia | The Gambia | Argentina | India | Kyrgyz Republic | Ukraine | Cameroon | Mexico | Grassroots Initiatives Home Page

(Banner Photo: An Internet cafe in The Gambia. Credit: Nichol Brummer/CC)