Internews is working in Haiti to limit the impact of inflammatory rhetoric, false news, and disinformation and strengthen the understanding of the challenges facing Haiti’s information environment. In Haiti, Internews partners with Panos Caribbean, a regional organization that works to amplify the voices of the marginalized through the media.

One of the main outputs of this partnership was an Information Ecosystem Assessment (IEA) of the Port-au-Prince area of Haiti. The assessment looked at specific communities’ access to information, how information is shared, what information is trusted and used, and what type of information is needed.

Read the Haiti Information Ecosystem Assessment

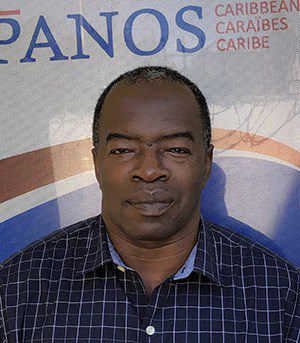

To gain more insight into the Haitian media landscape, Internews Program Assistant Nadia Lozano interviewed Jean Claude Louis, Coordinator for Panos Caribbean, also known as Institut Panos.

(The transcript of the interview has been edited for clarity.)

NL: How do you view your role in this project? What is interesting for you about it?

JC: The goal of the project is aligned with Panos’ philosophy and mission which is to promote debate and ensure that local people, especially marginalized communities, have access to information and solutions. When we were approached with the idea of the project, it was a no-brainer. This is something that Panos always wanted to do but did not have the funding to accomplish before. Knowing that Internews wanted to do something like this was a “godsend situation.”

The project was also a very good experience for me in the sense that, as leader of the project, I had the opportunity to involve my network of youth and other people of different backgrounds that I had been working with.

Some of the people that were invited to focus groups or interviews are very “modest people” who have never had the opportunity to sit down with somebody that would listen to them. We invited people who were sometimes just street vendors, and for them it was an enriching experience. For the youth, it was challenging because of COVID, but they were very enthusiastic when we told them they could interview people online using their phones or devices. It was a completely new experience for them. Many expressed interest in continuing to work with Panos. It has helped grow this network to build an even larger network of youth interested in this kind of work.

The project has also helped to promote debate, something that is lacking in Haiti. People don’t sit together to discuss issues, and this is causing political chaos. Public debate and discourse would help solve many issues. Taking [others’] views into consideration and sharing them with the entire population is a good place to start.

NL: Can you tell us your thoughts on the current media ecosystem in Haiti and the biggest needs and challenges you see? How do you see this project as helping/contributing to overcome those needs and challenges?

JC: The project is opening the eyes of many media managers and other media players in Haiti. The Haitian media landscape consists of just one private daily printed newspaper, a few weeklies and approximately 300 radio and TV stations that operate legally. Haitian journalists are underpaid and often lack the capacity and the resources to report on issues that require in-depth analysis, time, and research.

Over the past few years, there has been more media in Haiti, but the quality of information has not improved. People still rely on the media for information, but often cannot find the information they need. I think there is a lot of effort that needs to go into improving this in Haiti.

Media education is needed. Many people are now realizing that the information they’re consuming is not always accurate. The [Information Ecosystem Assessment] is bringing a new dimension of knowledge to understand communication and information in Port-au-Prince.

It should be publicized and shared with media owners, managers, stakeholders, and the youth.

The media and the authorities must listen to the population in order to meet their information needs. There are many gaps and misinformation fills those voids. It is necessary to promote media and information education.

NL: What do you see as some of the short-term and long-term impacts of this project in the Port-Au-Prince community?

JC: People need to learn to trust sources of information but at the same time, these sources of information have to provide good, trustworthy information. Haitians are secretive about information, especially the government. Haiti is a rare country in that, as of today, has not ratified the law to access of information.

In the long-term, there are many information needs that are not met in Haiti. In other countries, when people have a health issue, the first thing they do is go online and find information on the internet, but in Haiti, people do otherwise. Haitians think that somebody put a curse on them – and the media has a lot to do in this area since they provide mythical information about health.

Haiti is one of the countries most affected by the impact of climate change, but you don’t hear those issues debated or discussed in the media, and when they do, it’s mostly from scholars. We expect the study will push or promote information that people don’t currently get, like complex health information or information about issues like climate change. The public tends to forget these issues without continuous media coverage. Reporting on the environment or healthcare can be difficult because it requires scientific knowledge that journalists often lack. Preparing guides that explain some key concepts and issues, as PANOS has done in the past can help. Good reporting can influence actions taken by individuals and the government.

If you want to promote an open society, information must be free and useful.

One aspect that is very important is social media. In the past, social media has been used to demonize women, so in the long term we expect this study will help with these kinds of issues.

NL: Moving forward, what do you think should be the next steps in supporting Haitian media to thwart misinformation and disinformation?

JC: Making the [Information Ecosystem Assessment] more accessible to the public. Focusing on media managers because a big chunk of the population still relies on them for information and they have to make an effort to ensure they provide good information. They cannot relay information they don’t verify like many are currently doing. They should train their journalists to differentiate fake news from truth and provide a toolkit with advice and guidance on how to manage information.

We should also reach out to politicians and educate them on the media, show them they have a social responsibility. Based on Panos’ experience, which was strengthened by this project, teaching youth basic information helps them perform well at school because they have new ways to express themselves and they are able to convey their needs. In recent years, I have been working and developing activities for hundreds of young men and women, encouraging them to actively participate in the community via the media. Various workshops and practices that I have developed have trained young people in print journalism, radio and video reporting, and photography, and allowed participants to produce programs and reports.

What makes this work representative beyond the pandemic is a set of questions that Haitian society has not always asked or debated: Does the media disseminate quality information, are the sources reliable? What is quality information when we know that sports, music and politics occupy most of the media space?

As for other social topics, AYIBOPOST is perhaps one of the few media to go into the heart of Haitian society to explore information/subjects that are taboo. There is a lack of thematic, specialized programs, and the media needs to invest to bring this information to the public. For example, misinformation should be the subject of deep reflection and debate through the media.

NL: What is your biggest takeaway from this experience so far? Any final thoughts?

JC: Because of this study, many journalists and media are now asking how they can get more involved with Panos or Internews.

Many media are in a precarious situation where they can’t even pay for staff, but through experiences like this one, we can support certain media, certain journalists to ensure they provide good information for the population.

Even though media is impacted by the political situation and there is so much polarization in the media, these experiences might open doors for Panos and Internews to do more with media managers to make sure that the truth is provided to the people. The media can promote progress by raising awareness of issues and by giving a voice to the marginalized.

Internews has more than 10 years of experience working in Haiti in collaboration with local journalists, local organizations and authorities, and the international community. Since early 2020, Internews has been working to improve the information landscape through its Thwarting Disinformation and Promoting Quality Information in Haitian Media project.

Jean Claude Louis has been working in development for more than 20 years, starting his career with World Vision Haiti where he developed a passion for working with marginalized populations. Jean Claude has worked for several non-governmental organizations and has extensive experience in developing and implementing training courses on under-reported issues for journalists. He is currently the Coordinator for Panos. He is a founding member of the Centre of Communication on HIV/AIDS in Haiti, the Haiti Club Press and a member of the Association of Caribbean Media Workers (ACM).